CAROLINA GOLD FROM WEST AFRICAN KNOWLEDGE

South Carolina has a history closely linked to agriculture and the bounty of our rich and fertile soil. Cotton and tobacco were always principal inland crops, but during the mid-1800s rice was king in the South Carolina Lowcountry. It is not clear when rice first came to the SC coast, but one story has a British merchant vessel in need of repair putting into Charleston harbor and paying for the work with a bag of Madagascar rice seed. Seeds need a skilled hand to grow, and no colonial southern planter had the knowledge or experience to grow rice.

So how and when did rice take hold in the fragile marshes of the Lowcountry? And how did rice become the second-highest yielding crop, (only to sugar), sold through the European trade routes? How did Charleston become the rice capital of the south - to this day consuming more per capita than any other city in America? The answers all come from Africa; West Africa to be precise.

For many centuries the people of the African Gold Coast, (present-day Ghana), Sierra Leone and the Ivory Coast have cultivated rice. Rice has long been a staple in their diet and they are well-known for their ingenuity in engineering and building canals to irrigate field crops. Even the sweetgrass baskets are descended from handmade winnowing baskets used to separate the rice husk from the grain.

These Africans also happened to be in the crosshairs of the burgeoning mid-Atlantic slave trade triangle between Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Many peaceful tribes of West Africans were enslaved and shipped to the new world by English, Portuguese and Dutch merchants who prospered mercilessly on their human cargos. When the abilities of these Africans to grow and cultivate rice became known in America, they brought premium prices as enslaved people. Charlestowne, as it was called at the time, (after King Charles of England), was a major point of disembarkation and sale in the booming slavery trade. After depositing their human cargo, the ships were filled with rice, cotton, indigo, and tobacco bound for lucrative European markets.

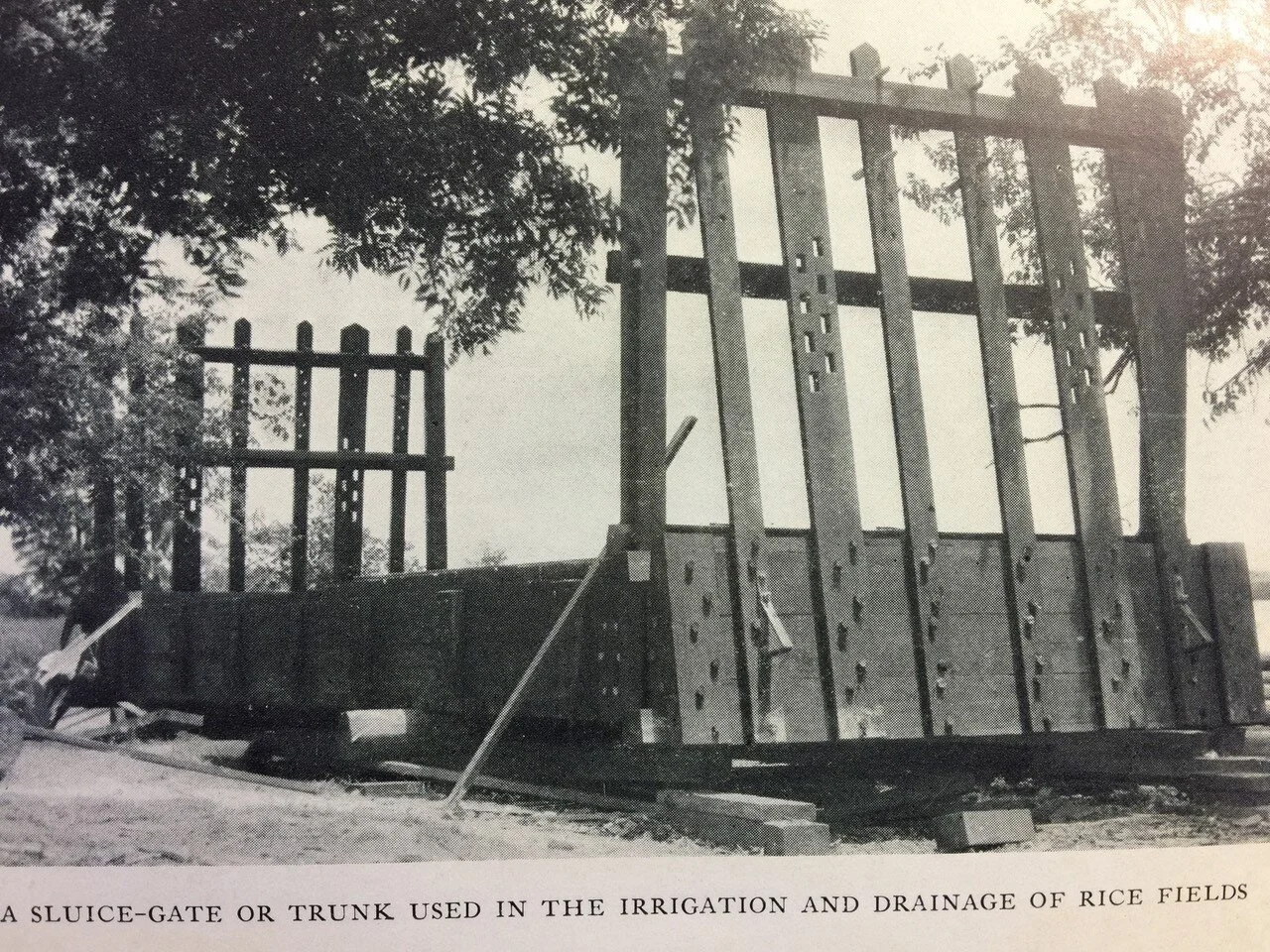

The flat, tidal Lowcountry marshes were well-suited to grow the golden grains that gave the rice its name, and that were so favored on the European plate. Rice is a very tedious crop to raise because it takes many hands to plant and most of the work is done in ankle, to knee-deep water. Fields must be drained and flooded four different times through the delicate growing cycle in order to yield a bountiful harvest. The dangers of snakes and malaria-carrying mosquitoes were always a risk to rice cultivation, and some field hands died as result of the harsh conditions in the hot summers, but west Africans proved more resilient to heat and disease than native American Indians.

Europeans developed quite a favorable taste for rice, and the supply could barely keep up with demand. Thomas Jefferson said that “Carolina Gold” was the finest rice that he had ever tasted, creating an endorsement that carried some weight in the marketplace. For a time in the mid-1800s, the Carolina Gold long-grain rice grown on southern plantations in the South Carolina Lowcountry commanded a higher price than most other export crops. During this productive time, the rice trade flourished and Charleston’s economy was larger than that of Philadelphia or New York.

South Carolina’s booming rice-driven economy was driven, not only by the muscle and sweat of the west African brow but by their knowledge and ingenuity to successfully grow and cultivate rice. When the war ended and the workforce was freed, rice came to a grinding halt as a “profitable” venture in the Lowcountry. Hundreds of acres of rice grew right here in Beaufort County at Garvey Hall Plantation. Some remaining canals are still in full view from highway 17 on the drive up the coast toward Charleston; deep and permanent scars in the heritage and culture of our collective and storied past.

Kelly Logan Graham is Executive Director of the Bluffton Historical Preservation Society, the non-profit group who own and operate the Heyward House Museum and Welcome Center. Call 843-757-6293 or visit HeywardHouse.org.