SOUTH CAROLINA'S 'BACK RIVER' OF RICE

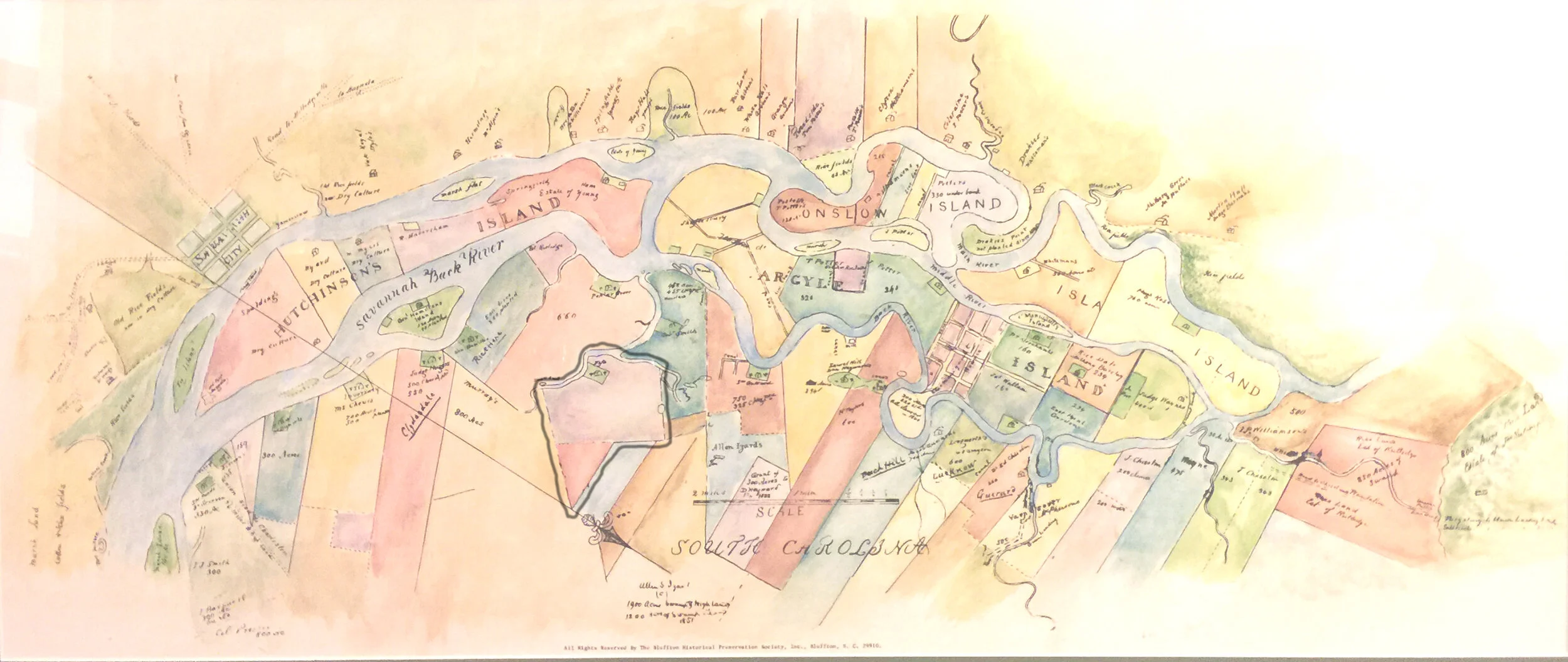

As you approach the Savannah River's Talmadge Bridge from the South Carolina side, the wide vistas of golden marshland that make up today's Savannah Wildlife Refuge seem as if they have always looked this way; but before the Civil War, these vistas contained more than 40 large rice plantations. The illustrated map from 1851 shows the carefully divided plantations, each owned by a wealthy southern planter, who visited only occasionally, leaving the overseeing to the appointed "drivers", who were trusted and rewarded for keeping the enslaved workforce on task. The great Savannah River that flows past the port city has two little sisters, the middle and back rivers, which fork and meander through the South Carolina marshes, creating a virtual shipping highway for the commerce of these perfectly positioned rice plantations.

One plantation that is shown on the map, is Fife Plantation, where Daniel Heyward inherited land and waterway access to the Savannah River. The "back river," wound its way along the South Carolina border, creating Hutchinson's, Onslow, Argyle and Isla Islands; all perfect for growing rice. Some of the richest and most powerful men are noted as owners on the many plantations drawn on the document. According to the original drawing, many of the planters "owned homes in Oakatee", (then a half of a day's ride away), where they would have spent most of their time. Many hands were required to work the rice fields, and 251 enslaved workers are listed in the hand-written list of names, sexes, ages and work assignments. Note the drivers, cooks, children's nurses, field workers and do. (domestic house workers), on the list, some noted as having been brought from Heyward's Combahee plantation, near present-day Okatee.

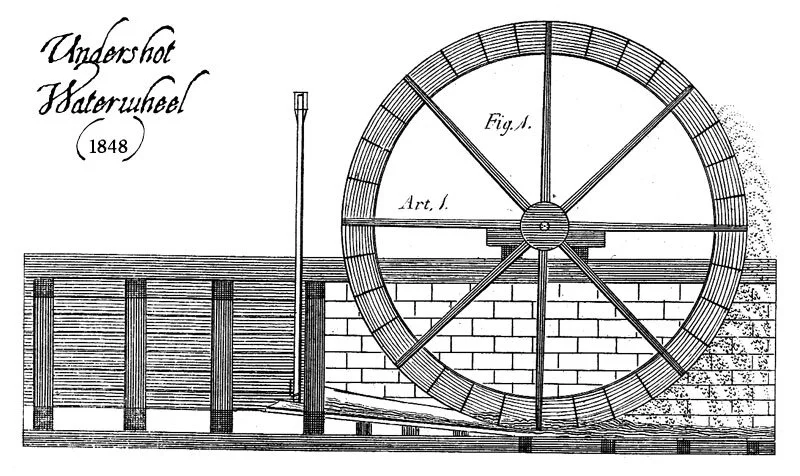

On the water's edge of each plantation, a green square indicates the location of the mill pond, where rice was gathered and milled for shipping. The location on the water provided more than the necessary transport by boat to market, it also provided the 'engine' that provided the power to mill the rice. An ingenious system that utilized hand-dug trenches, gates, and an undershot waterwheel, meant that during about four hours of the incoming tide, the power of the rushing water would spin the wheel. The gears and pulleys attached to the wheel transferred power indoors to the mill, where the rice was cracked and separated from the hull, before being bagged for shipment. During slack times when the tides were changing, the mill was silent, but when the tide changed and began to rush out, the gates were opened and the undershot wheel was back in action for another four hours of tidal action. Careful monitoring, and sometimes, 24-hour operation of the gates and mill made for demanding work.

The location of these particular plantations is vital to the hydro-engineering that made the Lowcountry marshes perfect for growing rice. These plantations, like the city of Savannah, are located over 8 miles inland from the ocean, where the strong currents of the Savannah River's fresh water can be utilized for the rice fields. The water in this section of the river stays fresh and is elevated and lowered with the tides because of the ocean's tides. The absolute genius is that these twice-daily tidal flushes of fresh water provided the pump as well as the incredible amount of water that was needed to grow and cultivate a rice crop.

The power of the rice dollar speaks to us through this map, where planters invested in the "Carolina Gold" rush that made Lowcountry rice the most sought after in the world for a time. Indeed, rice commanded a higher price on the European market than any other cargo except sugar. Carolina Gold made Charleston, SC the richest burgeoning city in the new world, where rice exports from the port made many men wealthy.

Today, as you drive toward the causeway and the Savannah bridge, imagine the spreading fields of rice, the humanity that would be seen in every field, toiling in the soggy marsh and fighting the sun and mosquitoes. With the end of the war, some freed people actually stayed on the failing ricelands, having nowhere else to go. All that now remains are a few crumbling structures, some old gates, and a few mill stones that are sinking slowly into the pluff mud, mill stones that once created the rice boom.

Kelly Logan Graham is Executive Director of the Bluffton Historical Preservation Society, which owns and operated the Heyward House Museum, which is the official Welcome Center for the Town of Bluffton. Call 843-757-6293 or visit HeywardHouse.org. BHPS owns the copyright for the SC Rice Plantation Map, reproductions are available, please contact us directly for information.